Every time I’ve ever talked to a devout Christian about their faith, I get a strange sensation that I’m just talking to myself. I give some argument, they quote the Bible, and at some point I often just want to shake them and say “But don’t you see that doesn’t make any sense!?”

I can’t help but wonder if the debate on the existence of god is purely futile. I mean, for most religious people, when asked, they will tell you very proudly that there is nothing that you could tell them to make them change their minds.

Why?

In its most basic form, these beliefs just are not the end result of logical analysis. It’s revelation. How do you refute revelation? Not sure… more revelation? Honestly, what logical argument could be presented to a person who doesn’t presume to use logic as the basis for their beliefs and overall understanding of the world around them.

But then I realized something very simple and close to home. I used to believe in god unquestioningly. I used to be the person who would proudly declare that there was nothing I could be told that would change my mind, and look at me now. So what happened?

It should first be pointed out that you don’t change anyone’s mind in real time. If you do, you just witnessed a miracle, or the person really was on the fence and was tipping your direction at that. So don’t expect to change anyone’s mind during the conversation. What you can do though is plant tiny seeds of doubt with those you have contact. Let them make up their own mind, but give them some facts to work with. Because for as adamant as someone may be about having nothing that will change their minds about their faith, we are creatures who thrive in part on logic. It’s an element of how we learn things. If I present an argument that makes enough sense, it will lodge itself in your brain until such a time as it’s refuted, provided it’s a topic you find of interest. It’s those seeds of doubt, but more accurately, those seeds of knowledge, that do the real work. It just takes time for them to grow.

Religion, and Christianity specifically, has a well-oiled defense mechanism against logical proof of its invalidity. Because of this, even the most astounding evidence presented that would raise serious doubts about the claims of Christianity will be completely disregarded by many Christians. And it’s very simple: it’s the devil. Doubt is from the devil. Anything that appears contrary to the praise of god is the work of the devil. This, naturally, is ridiculous, but I can only say that because I no longer have belief that it is true. For those who believe in god, and who consequentially also believe in the devil, this makes perfect sense. The trouble is that this argument is completely unfalsifiable, which has for a long time been acknowledged to be the sign of a weak argument, not a strong one. But since the only retort to this argument is “No, it’s not the devil,” there’s nothing a skeptic can tell a believer to move beyond it. The conversation, for all intents and purposes, has ended.

Given such a road block (which is why I often feel like I’m just talking to myself in these conversations), how do you overcome it. I would simply posit that you don’t. Anyone who feels content in accepting the devil as the logical source of doubt in their life is not seeking greater knowledge and understanding of the world. They are mentally incurious, but more importantly, they do not want to gain any other knowledge of the world for fear that it might contradict what they already “know.” There’s no known cure to mental incuriosity, but fear is volatile. It’s shaky. This emotion could wane enough to allow ones mind enough time to entertain some thoughts contrary to their beliefs. If fear is the primary reason for using this argument, then the seeds of doubt planted via logical argument stand a chance at growing. Christians will openly profess a fear of god, so let’s hope that there are more of the devout motivated by fear than by the other option, which is something that I would call a mental deficiency.

Of course, this still doesn’t explain why a skeptic should go through all this trouble to change someone’s mind about something, but that will be a topic for another piece.

Posts Tagged ‘faith’

Is the god debate worth it?

February 19, 2012Tags:agnostic, apostasy, atheist, Christianity, doubt, existence of god, faith, god, religion, seeds of doubt, skepticism, social causes

Posted in Social issues | 1 Comment »

What if you’re wrong?

February 10, 2012Lately, it’s been a minor preoccupation of mine to write about my apostasy from the Christian faith. Blame it on the positive feedback I’ve received on previous pieces that keeps me coming back to this topic. I’ve inadvertently uncovered a hidden sect of unbelievers in the small, northern Minnesota town where I work for the local newspaper, who prior to reading my columns that are critical of faith were under the impression that they were the only ones who felt that way about religion. So after receiving a certain number of emails and phone calls from fellow non-believers who are so thankful for my public confessions, and how what I’ve written so far has given hope for the future of reason, how could I stop? Fairly high praise for a small-town newspaper reporter, wouldn’t you say?

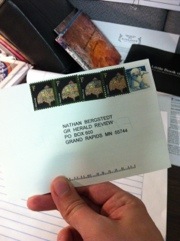

Yet, of course, there are the detractors. Most people aren’t exactly tickled to have their most cherished beliefs criticized anywhere, but especially not in a public forum. But this is Minnesota, baby! The general populace is far too polite to come out with the pitchforks and torches simply because the basis of their entire existence was insulted. No, they’ll stew in their own hatred, unwilling to let their neighbors witness their potential emotional instability, and eventually they’ll cap said feelings toward these ideas, forgive and forget, and move on, just in time to pull the hotdish out of the oven for dinner. Instead of the public lynching one could expect in other regions, here there’s the obligatory letter to the editor or two that file in, and most recently, a small litany of individuals who insist on praying for me (see “What I hear when told ‘I’ll pray for you’”).

Also recently was a visit from a local preacher, who one would expect is also praying for me. We met for coffee and discussed why it was I had renounced my former faith. Unsurprisingly, it eventually came up: what if you’re wrong? He was clever in the way he phrased the question, but it all comes out the same in the end. What are you going to do, an unbeliever in god, the creator of all things on heaven and earth, when you die and have to face your maker at the pearly gates?

In all honesty, I’m a little bit surprised that I haven’t been asked this question more often. It’s a common fear of the faithful, to leave the comfort of the church for whatever reason they may have and to ultimately find out when death’s winged chariot draws near their bedside that they had made the wrong choice, and that whatever benefits they received in life in no way balance to the tortures that await them as a member of the damned. I know I feared this as a Christian. And I know many of my fellow Christians from my former congregation felt the same. But it’s funny how no longer believing that hell exists can change your mind about having such fears.

The Bible, for all the clarity it generally lacks, is more or less straight-forward when it comes to who is going to hell. Blasphemers, of all stripes, are condemned, and from that point there are various denominations who widen the gulf to various degrees in regards to who else they feel are going to the lake of fire. So as one who openly renounced the savior of the world, not to mention the creator of the universe, I am therefore a more than worthy candidate for eternal suffering. Does this not worry me? Really, what if I’m wrong?

The question is most widely known as Pascal’s Wager. Blaise Pascal was a 17th century French mathematician who, in regards to the question of the existence of god, looked at the problem not ontologically or cosmologically, but instead prudentially.

“Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is… If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation that He is.”

It’s this line of reasoning that — if it doesn’t bring people to the faith — keeps people from leaving the faith. The converse would be that you wager that God isn’t, wherein if you lose, you lose everything.

Authors and thinkers on this matter have been quite eloquent before me. So let us first consult with Bertrand Russell, who said that upon meeting god would very succinctly state, “But sir, you didn’t give us enough evidence!” Taking it a bit further, and certainly more aggressive, would be none other than Christopher Hitchens, who first off refers to the wager as “religious hucksterism of cheapest, vulgarist, nastiest kind it is possible to imagine.” At the root, it has nothing to do with piety, let alone morality, and only hopes to win favors because it can, not because it’s right or earned. Even the religious should be insulted by such suggestions that the omnipotent creator of all things could be so easily connived as to allow the individual into heaven who on his lips said he believed but in his heart felt content that his bet was simply safe.

Hitchens went on, contributing further to what Russell would say when face to face with god, with, “Look, Boss, if it’s true what they say about you, that you’re an infinitely kind and forgiving and all-fatherly person – this is certainly what your fans keep saying – do you not have a little room in your obviously very capacious heart for someone who just couldn’t bring himself to believe in you, and really, honestly, truly couldn’t, as opposed to someone who spent half their life on their knees making fawning professions of faith because Pascal told them it was a good bet? Which of us is the more moral? Which of us is the more honest? Which of us is the more courageous? Which of us has the bluest eyes and is the most sexually attractive? Which of us has the real charisma here? I’m only asking.”

As poignant of answers to Pascal as both Hitchens and Russell have offered, they still don’t address the central point of the argument, that being that, assuming god is one who is easily given in to those who simply claim faith, one can gain all with a proper wager. For this, we’ll turn to neuroscientist Sam Harris, who once noted that, given the vast number of gods that have been worshipped and religions that have been adhered to over the centuries, and the incompatible claims made by each, that we should all expect to go to hell simply by probability. Pascal’s Wager, after all, makes the assumption that Yahweh is the one and only god, and that Christianity is the one and only system of belief. What if in fact the Muslims have had it right this whole time? Or the Jews? Or the Pagans? Or maybe it’s the Catholics who’ve been on the right path, and you happen to be Baptist, or vice-versa?

If it isn’t obvious by this point that the question of ‘What if you’re wrong?’ is a ridiculous question, then by all means it’s important that you as a person must go forth and believe the next theological claim given to you, because the possibility exists that it just may be correct.

The fear of the ultimate unknowable, what happens after our bodily death, won’t go away with the presence of a logic that further illustrates that we can’t know based on the laws of probability. Regardless, I think it’s important to ask ourselves is it not possible that we are simply not satisfied with the obvious answer of what happens to us when we die, that being that we cease to exist and our bodies decay to feed the next generation of life on the planet, and that this dissatisfaction has been mistaken for being insufficient?

Tags:agnostic, apostasy, athism, Bertrand Russell, christian faith, Christopher Hitchens, death, faith, family, god, life, Minnesota, Pascal's Wager, religion, Sam Harris, social causes

Posted in General, Social issues | 2 Comments »

What I hear when told ‘I’ll pray for you’

February 6, 2012In a semi-regular column space in the Grand Rapids Herald-Review, where I work as the Arts & Entertainment editor, I recently wrote a piece entitled “The experience of losing one’s religion.” In brief, it started by referencing a conversation I had with a fellow non-believer, and how this person wasn’t publicly out as such because of fear of repercussion from family. It was a lovely little piece in which I elucidated on all manners of details important to the up-and-coming apostate.

So anyway, I wrote it, it published, and people read it. Grand Rapids is in Minnesota – not quite the Bible belt, but it’s a small town that is plenty full of the devout. I knew what to expect. I had written pieces in the past that weren’t god-flattering. But this one was different.

On the morning of the Monday following the published column, a pastor from a local church actually came to the office to talk to me. There he was, a relatively young man who wouldn’t typically be confused with being a man of the cloth, what with his shaved bald head and leather coat, asking me if I knew Nathan Bergstedt. “Well, that’s me,” I responded. There was my column, being held in the right hand of this man of god. Not wanting to be accused of misrepresentation, he quickly drew his card for me. Sure enough, this leather-coated gentleman was a pastor, and he wanted to ask me some questions about my former faith. Well, I can certainly say that I was taken aback. Up to this point, I had never received a visitor on account of an opinion column.

I took off work for the next hour and we had coffee together. As it turns out, his primary reason for coming to see me was to ask me in person if I would come to his church the following Sunday. Flattered, I agreed to come. After all, he went through the trouble to visit me at my work; the least I could do is return the favor. After close to an hour of theological debate, he told me he would pray for me and we parted ways.

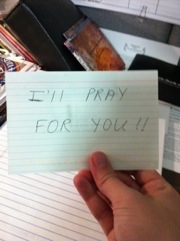

Over the next couple days, there were a few more responses. None of them were angry. But they appeared to come instead from a place that more closely resembled pity. Each instance was recognized by the ubiquitous “I’ll pray for you” statement.

I’LL pray for you. I’ll PRAY for you. I’ll pray for YOU. There’s something about this phrase that is taken as inherently polite in our society. It’s a phrase that almost immediately begs a “thank you” when told to you. How nice, this person is taking time out of their busy day to consider me and to ask god to help me. Now, if you don’t believe in god or the efficacy of prayer in general, there’s an automatic problem right up front with this saying. The second problem though, for me specifically in my situation, is that there was nothing wrong with me. I’m simply a person who doesn’t believe in god or the efficacy of prayer in general.

Here’s a picture. I’ve just been diagnosed with cancer. The doctors are doing all they can, but it doesn’t look good. Modern medicine, for all it has accomplished in others, is at best delaying my oh-too inevitable death, and some random person peeks their head into my room to say that they’ll pray for me tonight. This kind stranger is keeping me in his or her thoughts and has a deep desire that my body rid itself of the cancer that is slowly destroying it. How can one not appreciate that at some level? At this point, whether or not prayer works isn’t the matter. It’s the fact that someone who has never met me before, but who knows that all known worldly measures to cure me are not working, is hoping for a miracle so that I might be spared.

The above picture is pure fiction, but it’s a clear-cut instance where one praying for me would be more than appreciated. Coming back to reality, what does it really mean when someone says that they’ll pray for you, simply because you don’t share their beliefs? After spending just a short period of time considering this question, it strikes me more as a backhanded compliment than anything else. I mean, what if I’m happy the way I am? What if things are going well for me, and I’m mentally and emotionally satisfied with my life? Why would you hope for that to change? Sure, one can decide that the person really didn’t mean it that way, that they meant well, but that’s no excuse to be talked to in such a manner. A Christian Scientist parent who refuses to give their dying child drugs that could potentially save its life means well too, but of course this doesn’t excuse the ignorance-driven nearly-murderous inaction. So too does a phrase like “I’ll pray for you” stink of a veiled insult.

Fact of the matter is that the time of my apostasy has been the happiest and most fulfilling years of my life to date. It’s been a time of great self-discovery, as well as a time of understanding of the natural world that I had previously been less curious about. The idea of god was always just an assumed principle when it came to the world I viewed around me. I’ve heard this referred to as god-goggles before, and I’ll stick with that phrase. During the time that I consistently wore my god-goggles, an immediate solution arose for any problem that seemed at face value to be too difficult to readily answer, and that answer was typically “god did it.” And what’s more, even when I thought that the answer of “god did it” didn’t quite have the merit that it should have, that another answer seemed better, there was a fear that if I didn’t choose the “god did it” answer, that I was being sinful in thought. I was mentally bullied against my better judgment, and the feeling that I wasn’t being entirely truthful with myself never fully went away.

This feeling I had is what is typically known as one’s conscious, daemon, or inner critic. Though I didn’t have the courage to face myself on these questions and answers, my conscious knew that I wasn’t being honest, that I was merely going along with my immediate crowd for fear of being singled out as a doubting Thomas. But it’s worse than all that. This fear extended beyond what friends and family thought of me. No, there was also the fear that I would offend my creator to such an extent that I would be banished to hell for all eternity for daring to question him. This was exponentially worse than the possibility of offending friends and family. From the age which I began to understand the tenants of my former religion to any degree, it was driven home that the first thing in my life had to be my faith, and anything else in my life, including family, had to come second at best. All honor and glory to god.

But throughout this time, I kept noticing details of the world around me that didn’t line up with the teachings of the church. As an obvious example, we’ll use the existence of dinosaur fossils. Though my former church didn’t have an “official” stance on whether or not dinosaurs roamed the earth millions of years ago, it was widely understood amongst the congregation that the fossils were there to test our faith, because no such creatures were referenced in the Bible. It doesn’t need to be explained by me here that this is insanity to a wild degree. Though it wasn’t simply dinosaurs that made me question my faith, it was certainly a problem that contributed to my eventual seeking of a more honest truth about the reality in which we all live.

My desire for open inquiry, honest discussion, and general curiosity were forever at odds with my religious pretense. Like many, I became a master at compartmentalization, which put my faith in one box, and everything else in the world that I knew in another box, and never the twain shall meet. But in time, even this wasn’t satisfying. My faith was supposed to be number one in my life, and what’s more, it was supposed to be the solution to all my problems. It didn’t make sense that I should be as so incurious about it. If indeed the Bible and my Christian beliefs were the inherent truth of the world, revealed by god himself, then any propositions I were to throw at it shouldn’t be a problem.

For anyone who has ever come to this point in their life where they decided to take a critical look at what it is the Bible professes, it should be obvious enough why I came to the conclusions that I did.

It was this time that was the most difficult. Facing the facts that flew in the face of everything I had come to believe throughout my entire life, I was mentally torn on what to do, what to say, and even down to how to think. The conviction that Jesus was the savior of the world and that the universe was created by god in six days was unraveling, but I didn’t know how to deal with it. Ultimately, I spoke to someone, a relative stranger, who I figured could empathize to some degree and who had no real stake in my situation. This was a much needed pressure release, and probably saved me from doing something I would have very much regretted.

In the end, or more accurately, up to now, I’ve been much more satisfied with my life since shedding the dogma of unsubstantiated beliefs. I’ve had experiences that weren’t previously allowed to me, entertained thoughts freely that before would’ve been stifled by fear of a relentlessly power-hungry deity, and had the opportunity to view my friends and family in a light that was before not allowed to me, namely as viewing them as more important than a fear of god.

So praying that I find salvation in Jesus again? As far as anything my life experience has taught me, that life of mental servitude wherein I was driven to near madness on account of the inconsistencies that I was unable to question, let alone do anything about, is one of the worse things I could hope for myself, and yet apparently I should also consider it a good thing when someone tells me that they’ll pray for me to find my way back to this place. I politely say ‘No thank you’ to this suggestion. Less politely, I would rather use a phrase like ‘Fuck off,’ but there’s no sense in ending the conversation so abruptly. No, rather I would like to take some of these opportunities with the pious to let them know what I really think. It’s the reason why I had coffee with the pastor that day, as well as part of the reason why I took him up on his offer and attended his church service the following Sunday. After seeing the reverend pound away at the Bible before his flock, charismatically expounding the high ideals of faith in Christ, was I reconvinced? Obviously, I wasn’t in the slightest. No, instead I found it humorous at its high point, and disgusting at its low (I don’t care what anyone tells me, the story of how Abraham was about to murder his son Isaac, without question and simply because he was told to, has no redeeming value. If you think I’m wrong, consider what you would do if told to do the same to your children).

Regardless of what I think, saying “I’ll pray for you” will undoubtedly continue to be a polite phrase in our society. But with any luck, as those without faith in a creator or a redeemer become a larger segment of the population, and a more vocal one at that, perhaps the faithful will eventually feel less need to say such things after they find out that there really is little to pray for in someone like me. Unless of course they are actually wishing a winning lottery ticket upon me, but I’m not so certain they are.

Tags:agnostic, apostasy, atheist, bible, church, faith, god, Minnesota, pray, prayer, religion

Posted in General, Social issues | 4 Comments »

The experience of losing one’s religion

February 4, 2012By Nathan Bergstedt

Originally published in the Grand Rapids Herald-Review

Here’s a suggestion to writers out there: consider the topic of a recent conversation that you’ve had for a writing subject. A couple weeks ago, I had a conversation about freedom of speech that turned into an interesting column. And just earlier today, I had another conversation that got my wheels turning. And it was just the fodder I needed for another piece.

Anyone who has read my opinion columns with any regularity will probably know that I am a non-believer, a humanist, a free-thinker, a bright, an agnostic, an atheist. First off, as a minor tangent, I see all these terms as basically describing the same person. The individual can mince hairs as to how they like to define themselves. But for me, if I’m going to be defined theologically, despite the fact that I have no theology, any term that means “does not have a belief in god” will do just fine (for the record, I personally find Daniel Dennett’s term “bright” to be kind of stupid, though I say that with all due respect for his work in general).

Now that that’s been covered, let’s return to this conversation I recently had. It was with a fellow non-believer, who like me, grew up as a Christian. But unlike me, this person is not publicly out as an atheist. And the reason for that is because of fear of family repercussions. Part of this is because of the hassle that is apparently inevitable that would come in the form of a series of interventions in order to do some soul saving. But the other reason why this person has not told the family is because of concern for the mental well-being of the family, meaning not wanting them to have a constant fear for their loved one’s soul burning in hell forever.

Now, this person doesn’t believe in souls or some sort of consciousness that can exist beyond a body, nor in a place that this soul would go post-partum. So this fear does not belong to this person. But for those who do believe in hell, the idea that the soul of someone you care about is damned to spend eternity in fire is a horrible thought. Why would you want to trouble those you care about with this fear?

The easiest answer would be because it’s irrational, and it gives credence to the idea that a hell exists to attempt to protect people from the fear of it.

But more importantly, religion is a very important aspect of the lives of many people. So conversely, losing one’s religion is one of the biggest chapters one can experience in their short lives. To expect someone to keep this quiet from those they care about the most would be unrealistic to an extreme degree. The sensibilities of the faithful shouldn’t supersede the social and mental well-being of the person having the realization that all that they thought they knew was untrue.

I remember when I came out as an atheist. My family beseeched me to mind the feelings of my now ex-wife in regards to this topic. It was hard on her. Of course it was. But what about me? I had spent months wondering if my family was going to disown me upon learning that I no longer believed. And after I no longer went to church, all I had ever known by means of a support group was gone. I had lost contact with many friends, and my family wasn’t really sure how to talk to me. It wasn’t so much that they didn’t want to talk to me; they just weren’t sure how. But all this time, the burden was on me to mind the feelings of my wife, and no one expected her to mind how I felt to any similar degree. With the exception of a few friends, no one important in my life saw what I was doing as something right. I was finally being honest with myself about how I felt and thought, but the way it was approached by those around me was that it wasn’t something I did for myself, but something I did against others. I claim this is terribly unfair.

In the few years since all this happened, I’ve received many compliments on how I’ve come along, as well as for what it took to come to such realizations despite the social pushback.

But that doesn’t change the way the coming out experience happened. I find it terribly unfortunate and borderline disgraceful that those going through such profound changes in their life should have the extra burden of having to tiptoe around the delicate feelings of those whom they disagree. But I also can’t say that I necessarily blame my family for thinking and saying such things. The faith is what they know. Having a family member that is no longer part of the faith is new. And what’s more, they do in fact think that I’m wrong. I shouldn’t be surprised when I lacked support.

That doesn’t mean it’s the way things should be though. That’s part of the reason why I’ve written about my beliefs and experiences the amount that I have, because I think more people should be open to those who have no theology. Unfortunately, by the tenants of the religions of so many, there is no real way to reconcile the faithful with the faithless, if for no other reason because of the idea that one side will burn in hell forever. The stakes are simply too high. But these are the ideas of the faithful, not the faithless, so it should be their burden to deal with such claims, not vice-versa.

I love my family, and certainly care what they think. But I can’t let what they think dictate how I live my life. The last couple of years has been a wonderful time of self-discovery that I wish more people could experience. It’s hard enough to lose one’s religion, but in one man’s experience, it’s definitely worth it in the end.

Tags:agnostic, atheism, belief in god, burning in hell, Christianity, constant fear, daniel dennett, faith, family, free thinker, freedom of speech, friends, god, logic, losing, nonbelief, religion

Posted in Social issues | 9 Comments »